How Massachusetts Funds Transit (Not Just the T)

A guide to how Massachusetts state government finances public transit service across the Commonwealth.

By Meghan Volcy

As part of an ongoing webinar series on transportation policy in Massachusetts, Transportation for Massachusetts (T4MA) recently hosted three transportation budget experts for a timely discussion on how the Commonwealth funds its public transportation systems, from the subways of the MBTA to rural vanpools that connect small towns.

The event was part of the “People’s Caravan” series, which T4MA is sponsoring to give advocates a more detailed understanding of the state’s transportation history, funding, and policy as the state legislature returns to business in the new year.

Regional transit authorities

Alexis Walls from Massachusetts Public Health Alliance spoke to how Regional Transit Authorities (RTAs) are funded in Massachusetts (editor’s note: Walls is also a member of the StreetsblogMASS board of directors).

The state’s 15 RTAs provide paratransit and bus service outside the MBTA service area in gateway cities like Worcester, Springfield, Lowell, and Brockton. 55 percent of the state’s population lives in an RTA service area, including 16 percent of Black residents in Massachusetts, 34 percent of those aged 18-29, and 53 percent of households earning less than $50,000 annually.

Due to rising housing costs, people are being pushed out of bigger cities, being pushed out of MBTA service areas, and need RTAs for transportation equity and the ability to move, Walls argued.

The services provided by RTAs are critical for connecting people to their livelihoods. Operating funding, funds that cover day-to-day expenses like salaries, supplies, and fuel, comes from various sources like federal government grants, the state budget, local assessments, and direct system revenue (e.g., fares and ads).

However, most RTAs are moving towards fare-free models, reducing the presence of direct system revenue in the budget.

The state budget is an important place of advocacy for RTAs. Before the pandemic, an average of 39 percent of the typical RTA’s budget came from the state.

In the past, inconsistency in state funding created a pattern where RTAs try to implement improvements, then face insufficient state funding, and struggle to sustain services, sometimes having to cut it altogether.

Two years ago, though, the state supplemented its standard RTA funding with additional funds from the Fair Share Amendment, or the “millionaire’s tax.” With this critical legislation, state funding for RTAs has grown from $94 million in FY23 to $150 million and $160 million in FY24 and FY25, respectively.

In addition to general operating funds, RTAs also get grant money from the Fair Share pot that allows them to experiment with other programs to meet community needs. The Fair Free Grant provides $30 million to 13 of the 15 RTAs to offer fare-free service. The Community Transit grant provides funding to RTAs and other organizations to provide new connecting transit services, like the Quaboag Connector, a demand-response shuttle service covering nine towns in the Quaboag Valley in West Central Massachusetts.

In short, changes in funding significantly impact the programs that communities need. Walls provided a visual of this point, referencing a 2018 flyer that warned about cuts affecting RTAs, and how that would affect Sunday service, night and evening service, and the agencies’ ability to provide additional routes.

Brian Kane, Executive Director of the MBTA Advisory Board, presented an overview on his work representing the 178 cities and towns across Massachusetts in the MBTA service area.

The Advisory Board’s role is to advocate for these municipalities, with local executives of each community (mayors, town managers, etc.) serving as the board’s members. These 178 municipalities contribute $193 million annually to the MBTA, helping fund its operations.

Kane also spoke to how the MBTA is funded, what their main expenses are, and the challenges and future of funding.

The MBTA used to be funded by a cigarette tax, but since 2001, it has been primarily funded by a combination of the statewide sales tax, federal grants, state appropriations, local assessments, and fare revenue. Some of the MBTA’s biggest annual costs include employee wages and benefits, as well as contracting out commuter rail operations to the French company Keolis, costing the agency $578 million annually.

Kane then turned his presentation to the MBTA’s funding challenge in balancing its operating costs and infrastructure needs. In fiscal year 2025, the sales tax generated $1.465 billion for the MBTA, supplemented by a $314 million dollar state appropriation to address safety and hiring changes. However, the MBTA has to manage both day-to-day operations and building and operating large-scale infrastructure projects like South Coast Rail and the GLX project with this revenue, with most of the funding going to wages and labor-intensive activities.

The need for continuous borrowing, the uncertainty of future federal funding beyond 2026, and the end of state infrastructure support in 2029, presents a long-term challenge of financial instability for the T to manage daily operations, expansion projects, and infrastructure upkeep.

“The biggest single source of MBTA infrastructure spending is money that it borrows against its own future revenues,” said Kane.

So how did the T get here?

Kane blames the funding structure also known as “forward funding,” which started in 2000 and gave the T a 1 cent slice of the statewide sales tax. At the time, the statewide sales tax had grown by an average of 6.5 percent per year, but since 2000, the actual annual growth in sales tax revenue slowed considerably, and has averaged under 3 percent growth each year. This discrepancy between what was expected and what actually happened landed the MBTA in this spot.

Additionally, the MBTA took on considerable debt to pay for various projects associated with the Big Dig. The T is still paying back its debts on those projects, which will cost the agency an additional $8 billion by the time they’re finally paid off.

Rural ridesharing

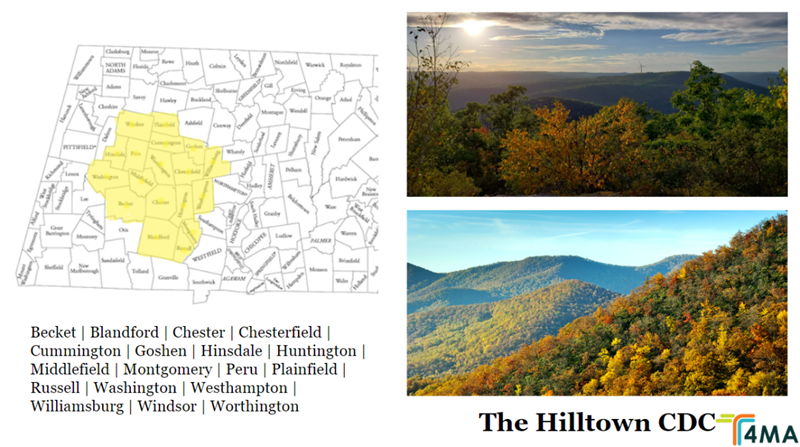

Joan Griswald, the Director of Community Programs at the Hilltown Community Development Corporation (Hilltown CDC), spoke to those municipalities that aren’t covered by the RTAs and MBTA approach mobility.

The Hilltowns encompass numerous rural towns, and while their region is part of the FRTA region, it is not part of any fixed route service. Overall, 700,000 people reside in rural Massachusetts, supplying food and recreational activities for the rest of the state, yet they still receive less infrastructure money and support from the state and federal levels and have unmet needs that they meet locally. The Hilltown CDC in Chesterfield, MA, was one of those agencies created to support the needs of the region, including microtransit.

Microtransit, Griswald explains, is an alternative to larger transit systems serving densely populated areas, using smaller vehicles to provide transportation. The Hilltown CDC took over transportation in Goshen, MA seven years ago because the local municipality was not meeting the residents’ transportation needs, and now covers transportation in 11 Berkshire hill towns.

Being the only public transportation option for residents to get connected to their health care, food sources, and other aspects of their livelihoods, the Hilltown CDC partners with the Franklin Regional Transit Authority (FRTA) to keep two vans on the roads, with a third van from MassDOT on the way.

Griswald has also seen an uptick in younger people moving to the hilltowns because of its affordability, and is wary about the microtransit’s current operating budget, and whether it will be able to provide for more riders.

In response to the service area’s population growth, the Hilltown CDC has been fundraising for support from local hospitals, has partnered with T4MA, and entered a “unit rate contract” with the Highland Valley Elder Services, allowing them to provide more services for elderly populations. However, questions about the funding for Hilltown microtransit remain.

Griswald notes that the Hilltown CDC also engages in housing, healthcare, food, and economic justice work in rural communities, and highlights that there is a lot of need, particularly in the Southern Hilltowns.

She also expresses concern about the new administration coming in, constantly engaging with legislators trying to get an idea of what to prepare for in terms of future funding priorities.

Griswald lays out her hopes for actualizing transportation justice: “Transportation justice means that I can accommodate anybody who makes an inquiry about needing transportation. I want to be able to provide them with a ride.”