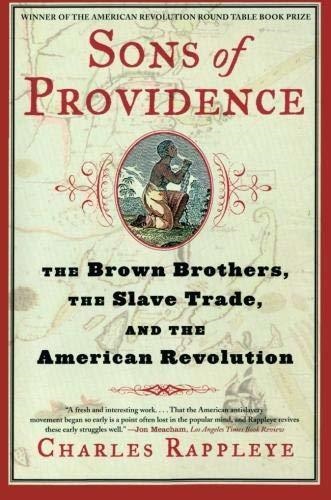

This is the must-read book for our times.

We have three hardback copies of this long out-of-print book, which

Ray Rickman consulted on. $35

If you wish a copy, please email: StagesofFreedom@aol.com

and we will provide a link to purchase it. Sales benefit Stages of Freedom’s work!

“Mr. Rappleye’s book on the Brown family and its deep involvement in slavery and every aspect of Rhode Island life may be the best book ever written on an Americican family.”

– Ray Rickman

Set against a colonial backdrop teeming with radicals and reactionaries, visionaries, spies, and salty sea captains, “Sons of Providence” is the biography of brothers John and Moses Brown, two classic American archetypes bound by blood yet divided by the specter of more than half a million Africans enslaved throughout the colonies.

To purchase a copy, please email: StagesofFreedom@aol.com

Read Robb Dimmick’s

Providence Journal reply to

Sylvia Brown’s defense of her

slave dealing ancestors:

My Turn: Robb Dimmick

Words alone can’t scrub slavery’s stain from

Brown name.

Providence Journal, July 2, 2020

Isn’t it a shame that Sylvia Brown in her recent My Turn piece (“The truth about the Brown family and slavery,” Commentary, June 26, see below)), felt it imperative to “seize this important moment,” an amorphous moment she never identifies, for her own selfish purpose of defending her family name, because mentioning that this “moment” is one bursting with Black angst, anger, fear and pride would implicate the Browns even more in the very sort of institutional racism that this “moment” is marching against. Insensitive as she is, she has to affront us with falsehoods in an effort to rescue her family reputation. Sometimes, the truth is a lie.

Ms. Brown says Brown University was named for John Brown’s nephew, Nicholas, an abolitionist, and not him, a slaver; that’s true. But John Brown and brother Moses, who had not yet divested himself of the slave trade, in a race against Newport to see which could raise more funds to claim the college, won the contest with their own slave dollars, and those of plantation owners they solicited in the Deep South. And with their prize purse, the colonial legislature granted the Browns a charter, and the edifice, (now known as University Hall, the largest building in Rhode Island at the time), was built from the ground up on their Providence property by the hands of enslaved people: Pero, Job and Mingow, to name a few.

In 1804, Nicholas Brown, with a significant donation of inherited money from the Brown family’s lucrative China Trade (run on refitted slave ships), the slave trade itself, and child labor at Slater Mill, was entitled to strip the College of Rhode Island of its name and emblazon it with their own. For more than 200 years, the Browns dominated its operation. Thirty members of Brown University’s first governing board owned or captained slave ships.

It is impossible to distance the exceeding wealth of today’s Brown family from foundational slave dollars. Parading a panoply of family members who may have done a little better on race in “reserved, discrete” ways over the last 200 years does not absolve the Browns’ deep participation in America’s original sin. Wouldn’t it be nice for Ms. Brown’s family to “seize the moment,” as so many corporations, institutions, foundations, and private citizens the nation over have, and share some of its wealth with Black causes here in Rhode Island, perhaps through a fund at the Rhode Island Foundation. Then she, too, could stand alongside some of her good relatives as a troubadour for justice.

As a Mayflower Compact family descendant, my roots run as deep as Sylvia Brown’s, and I desire nothing more than to see this country, built on slavery and by enslaved people, right its wrongs, abolish Jim Crow laws, end police brutality and dismantle systemic racism.

Robb Dimmick, of Providence, is co-founder of Stages of Freedom and author of Disappearing Ink: A Bibliography of Books by and about Rhode Island African Americans

My Turn: Sylvia Brown

The truth about the Brown

family and slavery.

Providence Journal, June 25, 2020

Much has been written in recent weeks about Rhode Island’s dominant role in the transatlantic slave trade. Most articles mention “slave traders that included the prominent Brown and DeWolf families” or “the fortunes made by the Brown family in the slave trade.” As the eldest of the 11th generation of Browns in Rhode Island, I want to seize this important moment to clarify why blanket statements about families are both incorrect and often harmful to a cause.

Two-hundred-twenty years ago, my brash, flamboyant great-great-great-great-great uncle, John Brown, stood up in Congress to defend the right of American merchants to engage in the slave trade. Some 150 years later, my grandfather, as assistant secretary of the Navy, was instrumental in desegregating the U.S. Navy during the Truman administration. His grandfather actively supported abolition initiatives before the Civil War and reconstruction efforts thereafter. That ancestor’s father was vice president of the Providence Abolition Society. And that man’s father (John Brown’s eldest brother), having deeply regretted his participation in a horrific 1764 slaving venture, made sure his sons were apprenticed to and mentored by one of Rhode Island’s foremost abolitionists, George Benson.

But the shadow of this long-dead uncle hangs heavy over my branch of the Brown family and misconceptions continue, notably that John Brown “founded Brown University with money made in the slave trade.”

Here are the facts: The College of Rhode Island was founded in 1764 by the Baptist Association of Philadelphia with funds raised all down the Eastern seaboard.

John Brown and two brothers were indeed involved as signatories of the charter (along with 57 others), and in providing land and a building for the college’s relocation to Providence in 1770. The John Brown story ends with his death in 1803. Forty years after its founding, the college was renamed Brown University to honor Nicholas Brown Jr., an ardent opponent of the slave trade.

Yes, he was a successful merchant in an economy fueled by slavery. But he forbade his captains to engage even remotely with trafficking and ensured his family’s Providence Bank did not lend to slave traders. He was also a fierce enemy in both business and politics of the DeWolf family.

It’s Nicholas Brown’s descendants who have been benefactors of the university, the city of Providence and the state of Rhode Island, generation after generation. And it is of their track record that I am justifiably proud.

I remember well my naval officer father’s sense of honor at being second-in-command to America’s first African-American admiral when Samuel Gravely Jr. was promoted in 1971.

I also remember my shock in 2004 when a speaker at Brown University’s first public forum on slavery and justice announced, “There were no good Browns …” That comment led to a decade of research and my book, “Grappling With Legacy.”

Controversial characters like John Brown may make for better stories than my rather reserved, discreet, direct ancestors. But, in times like these, when sensitivities run high, getting the facts straight is more important than ever.

Sylvia Brown, author of “Grappling With Legacy — Rhode Island’s Brown Family and the American Philanthropic Impulse” (Archway 2017), is a philanthropy adviser and donor educator.