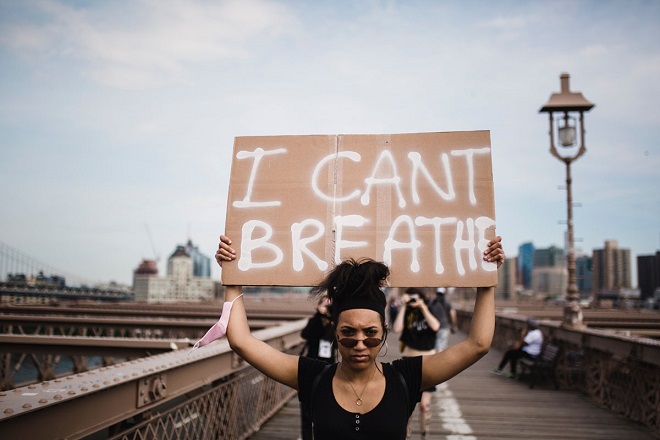

“Air pollution and rollbacks to environmental protections and regulations make it hard for black people to breathe,” says Robert Bullard, the “father of environmental justice” and founder of the non-profit National Black Environmental Justice Network (NBEJN). Credit: Pexels.com.

Dear EarthTalk: Is there any overlap between the #BlackLivesMatter and Environmental Justice movements?

There certainly is: “Environmental injustice”—defined as the unfair siting of pollution and other environmental ills in proximity to certain groups based on race or income status—is on a list of 12 issues Black Lives Matter (BLM) considers pressing right now as part of its #WhatMatters2020 campaign.

“Environmental racism kills. Air pollution and rollbacks to environmental protections and regulations make it hard for black people to breathe,” says Robert Bullard of the non-profit National Black Environmental Justice Network (NBEJN).

Sammy Roth reports in the Los Angeles Times that there are many links between ecological degradation and inequality: “Consider water contamination in predominantly black and brown communities, such as Flint, Michigan, where experts say the drinking water crisis was rooted in systemic racism.” She cites a February 2020 Los Angeles Times investigation that found Black, Latino and low-income California residents to be especially likely to live near polluting unplugged oil and gas wells. And many studies show that people of color are more likely than whites to live near power plants, oil refineries and landfills. “In the U.S., the best predictor of whether you live near a hazardous waste site is the color of your skin.”

To add insult to injury, climate change is already hitting people of color harder than others in the U.S., a fact not lost on BLM. “We are not saying that white people do not feel the impact of climate change,” BLM activists Patrisse Cullors and Nyeusi Nguvu report in a Guardian op-ed. “We are saying that if you are black then you are more likely to die as a result of it—and, if you survive, are more likely to struggle to replace what was lost and will receive little support in doing so.”

What can we do to reduce or eliminate this insidious form of injustice? Activists blame governments as well as corporations for discriminating against racial minorities in deciding where to put pollution sources. Attending local zoning or planning board meetings in your city or town—and speaking up against what’s not right—would be a good start. But, of course, there is more to the story.

“While it is clear that discriminatory siting plays a role, other causes may help explain both the behavior of firms and the disparate environmental harms experienced by low-income populations and minorities,” reports Shea Diaz in the Vermont Journal of Environmental Law. “Regulators may enforce environmental laws and regulations unequally, affected communities may lack political power, and market dynamics may drive both businesses and residents to low-cost real estate.” According to Diaz, it’s important to understand the contribution of each of these to environmental injustice because they may call for different policy responses. And only when a majority of elected officials agree can we begin to enact laws that regulate how governments and companies treat minority and low-income communities.

CONTACTS:

“The toxic legacy of old oil wells”

As Rising Heat Bakes U.S. Cities, The Poor Often Feel It Most

“Getting to the root of Environmental Injustice”